How big is an atom? A simple question maybe, but the answer is not at all straighforward. To a first approximation we can regard atoms as 'hard spheres', with an outer radius defined by the outer electron orbitals. However, even for atoms of the same type, atomic radii can differ, depending on the oxidation state, the type of bonding and - especially important in crystals - the local coordination environment.

Take the humble carbon atom as an example: in most organic molecules a covalently-bonded carbon atom is around 1.5 Ångstroms in diameter (1 Ångstrom unit = 0.1 nanometres = 10-10 metres); but the same atom in an ionic crystal appears much smaller: around 0.6 Ångstroms. In the following article we'll explore a number of different sets of distinct atomic radius sizes, and later we'll see how you can make use of these 'preset' values with CrystalMaker.

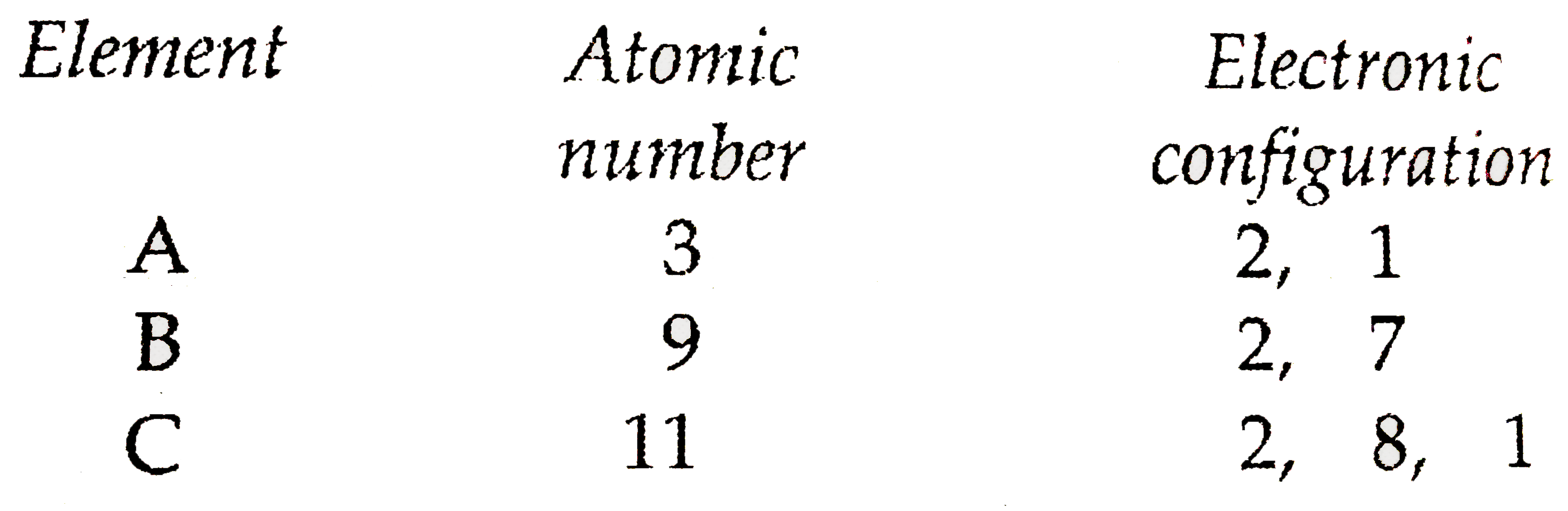

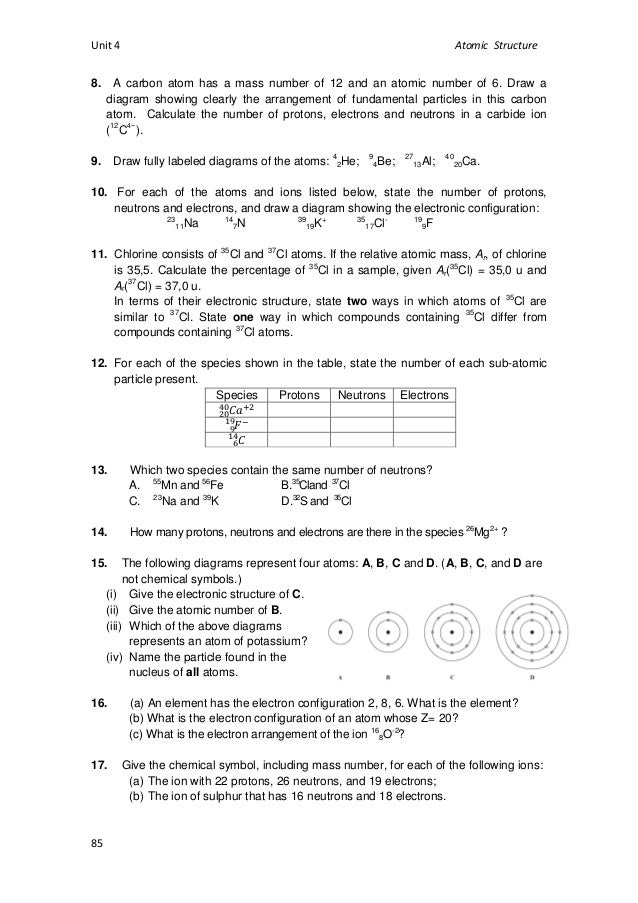

Therefore the C electron configuration will be 1s 2 2s 2 2p 2. Video: Boron Electron Configuration Notation The configuration notation provides an easy way for scientists to write and communicate how electrons are arranged around the nucleus of an atom. The atomic mass is useful in chemistry when it is paired with the mole concept: the atomic mass of an element, measured in amu, is the same as the mass in grams of one mole of an element. Thus, since the atomic mass of iron is 55.847 amu, one mole of iron atoms would weigh 55.847 grams. Nitrogen atom has an atomic number of 7 and oxygen has an atomic number 8. The total number of electrons in a nitrate ion will be (a) 8 (b) 16 (c) 32 (d) 64 Ans. If molecular mass and atomic mass of sulphur are 256 and 32 respectively, its atomicity is (a) 2 (b) 8 (c) 4 (d) 16 Ans. The atomic number of an element is 17.

Atomic Radii

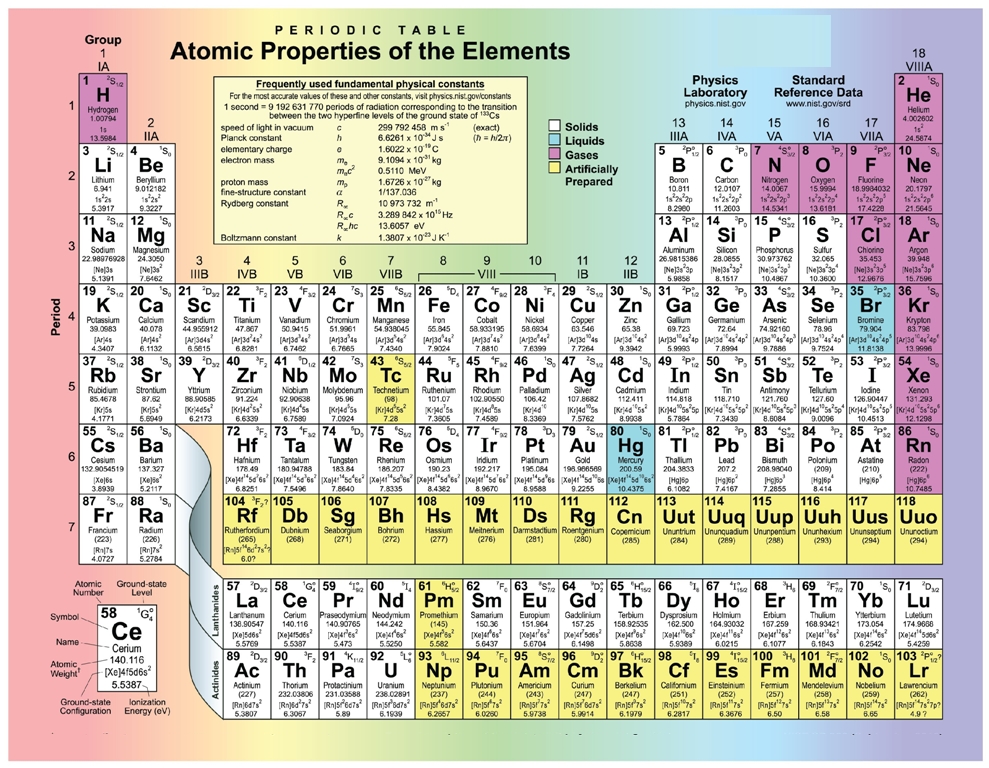

Atomic radii represent the sizes of isolated, electrically-neutral atoms, unaffected by bonding topologies. The general trend is that atomic sizes increase as one moves downwards in the Periodic Table of the Elements, as electrons fill outer electron shells. Atomic radii decrease, however, as one moves from left to right, across the Periodic Table. Although more electrons are being added to atoms, they are at similar distances to the nucleus; and the increasing nuclear charge 'pulls' the electron clouds inwards, making the atomic radii smaller.

Atomic radii are generally calculated, using self-consistent field functions. CrystalMaker uses Atomic radii data from two sources:

VFI Atomic Radii:

Vainshtein BK, Fridkin VM, Indenbom VL (1995) Structure of Crystals (3rd Edition). Springer Verlag, Berlin.CPK Atomic Radii:

Clementi E, Raimondi DL, Reinhardt WP (1963). Journal of Chemical Physics 38:2686-

Covalent Radii

The covalent radius of an atom can be determined by measuring bond lengths between pairs of covalently-bonded atoms: if the two atoms are of the same kind, then the covalent radius is simply one half of the bond length.

Whilst this is straightforward for some molecules such as Cl2 and O2, in other cases one has to infer the covalent radius by measuring bond distances to atoms whose radii are already known (e.g., a C--X bond, in which the radius of C is known).

CrystalMaker uses covalent radii listed on CrystalMaker-user Mark Winter's excellent Web Elements website.

Van-der-Waals Radii

Van-der-Waals radii are determined from the contact distances between unbonded atoms in touching molecules or atoms. CrystalMaker uses Van-der-Waals Radii data from:

Bondi A (1964) Journal of Physical Chemistry 68:441-

Atomic-Ionic Radii

These are the 'realistic' radii of atoms, measured from bond lengths in real crystals and molecules, and taking into account the fact that some atoms will be electrically charged. For example, the atomic-ionic radius of chlorine (Cl-) is larger than its atomic radius.

The bond length between atoms A and B is the sum of the atomic radii,

dAB = rA + rB

CrystalMaker uses Atomic-Ionic radii data from:

Slater JC (1964) Journal of Chemical Physics 39:3199-

Crystal Radii

Perhaps the most authoritative and highly-respected set of atomic radii are the 'Crystal' Radii published by Shannon and Prewitt (1969) - one of the most cited papers in all crystallography - with values later revised by Shannon (1976). These data, originally derived from studies of alkali halides, are appropriate for most inorganic structures, and provide the basis for CrystalMaker's default Element Table. The data are published in:

Shannon RD Prewitt CT (1969) Acta Crystallographica B25:925-946

Atomic Number Of C

Shannon RD (1976) Acta Crystallographica A23:751-761

The Colours of Atoms

Colour-coding atoms by element type is an important way of representing structural information. Of course, atoms don't have 'colour' in the conventional sense, but various conventions have been established in different disciplines.

Many organic chemists use the so-called CPK colour scheme These colours are derived from those of plastic spacefilling models developed by Corey, Pauling and (later improved on by) Kultun ('CPK').

Whilst the standard CPK colours are limited to the elements found in organic compounds, CrystalMaker's VFI Atomic Radii, CSD Default Radii and Shannon & Prewitt Crystal Radii Element Tables provide a more diverse range of contrasting colours.

Atomic Number Of Cl

Organic Structures Alert! CrystalMaker's default Element Table is the Shannon & Prewitt 'Crystal' radii, which is appropriate for most inorganic structures. When working with organic structures, one of the covalent or Van-der-Waals sets will be more appropriate.